My Father and his family: Eccles to Whaley Bridge

Written by Charlie Hulme

Llandudno 1948: before I was born.

Father and Son, 1950s

5 Spring Bank Terrace, seen in 2017. It was sold in 2015 and has been comprehensively restored.

Mevril Springs Bleachworks

The Bennett and Jackson yarn bleaching works near the Mevril (sometimes spelled Meveril) spring was a late arrival on Whaley's industrial scene, constructed in 1901 and welcomed by locals, and the decline of the collieries in the area was causing employment.

I believe (comments welcome) that the cop-bleaching process; upstairs, winding machines operated by female staff transfer yarn on to 'cops' which are large bobbins which can be utilised directly by the customers on their looms. My mother's picture above, taken in the 1940s, with her sister Alice on the right, illustrates the procedure.

The business was a partnership of Charles E. Bennett, the son of John Bennett who had a calico printing works in Birch Vale, and Glossop-born John James Jackson, the manager of the Birch Vale works. Jackson made his home in 'The Oaks', a large house on Elnor Lane, Whaley Bridge. In 1914 the firm joined the amalgamation known as the Bleachers Association, which had been formed in 1900 from over 60 bleaching firms, but continued to trade under its original name

Charles Bennett was involved with several other textile businesses including the Ceba Down Quilting Company in Oliver Street, Stockport, which he purchased in 1879. An 1895 directory has 'Charles E. Bennett & Co., Bleachers & Sizers' operating in Birch Vale. The location of this works is not clear to me: was it part of the Bennett print works complex, or the Garrison bleach works lower down the river Sett?

Charles Edward Bennett married Hayfield-born Frances Amelia Eyre in 1883 and they moved from Birch Vale to a large semi-detached villa (still in existence) called 'Thornycroft' on Burlington Road in Buxton. He died in 1899 in London, before the Mevril works was completed.

Aerial view dated 1937, courtesy of English Heritage

The Bleachers' Association, which in 1963 became Whitecroft Industrial Holdings, closed the Mevril down works in the early 1960s, allegedly because the trade union called a strike for higher wages. As the textile industry in Britain collapsed, Whitecroft turned itself into a property developer, and still flourishes in 2017.

The works was taken over by the Dovedale Brick Company, which had an associated company called Whaley Bridge Proofing, which, among other products, proofed webbing for Army uniforms. Both companies appear to have ceased trading in 1973; latterly the building was divided into smaller units, before its final demolition to be replaced by housing including a street appropriately named 'Mevril Springs Way'.

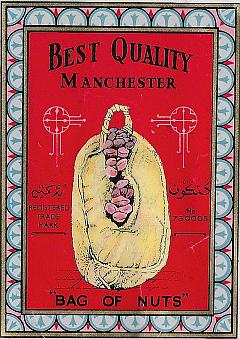

My mother's job at the Mevril was in the upstairs packing department, wrapping and labelling parcels of compressed yarn for dispatch; she saved a few of the labels which give an idea of their customers. Yarn was received from cotton-spinning mills, and bleached before being sent to weaving mills across the Empire.

Bingswood Printworks

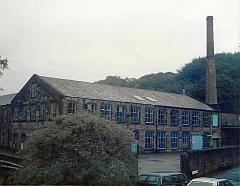

The printworks, whose buildings (seen above in 1968) are almost the only reminder in 2019 that textile works existed in Whaley, is named for nearby Bings Wood; the word Bings is said to mean a coal mine spoil heap.

The first mill on the site was built by a John Welch in 1853, but over the years there were many changes to the buildings; eventually the River Goyt was diverted to a new course to allow further construction. In the 1890s it was taken over by a firm which re-located from Ratcliffe, Lancashire, bringing with them workers who were housed in 24 new houses which formed Bingswood Avenue. In 1900 the firm joined the conglomerate known as the Calico Printers Association (CPA) which ran the business until, by then known as Whitecroft, closed it down in the 1950s and it was later divided to become an industrial estate. The surviving print works buildings are said to date from around 1912-15.

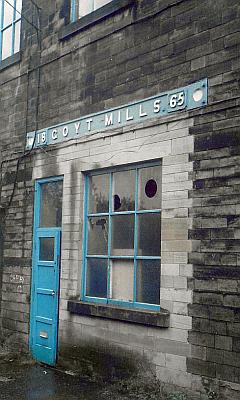

Goyt Mills

The Goyt Mills, located adjacent to the river of the same name, which seems to have been diverted slightly to make space , was built in 1865-66 for a Mr Adshead who is said to have lived in the village at Horwich Bank, as researchers have had trouble locating more details. It was a stone-built single-storey weaving shed, with a two-storey building in front in which ancillary processes took place. It was known to all in Whaley as 'The Shed.' It had its own railway sidings, connected to the Whaley Bridge section of the Cromford and High Peak line. One siding served to supply coal for the boiler house, and another, abandoned at an early date, ran alongside the main building, to a shelter for loading or unloading materials.

After some early troubles, which included on one occasion the burning by the workers of an effigy of the manager, the mill settled down to a workaday existence, employing many local women to tend the powered looms; it was claimed to be the largest one-room weaving shed in Britain. It appears to have also engaged in cotton spinning, and its listed as such in a 1910 directory.

This aerial view shows the weaving room with its north-light roof. Old maps show that it was extended twice during its working life.

The view above was taken after closure. Like all such sheds of the period, the weaving area was a cacophony of noise when in operation, as the shuttles were knocked back and forth between the warp threads. Each weaver tended twelve (originally eight) semi-automatic looms, which would have been powered by overhead pulley and belt driven from a steam engine, but later electric motors were used.

In the 1960s my mother ran the works canteen, until the management decided to increase productivity by closing the canteen and providing drinks vending machines on the weaving floor, so she had to venture into the noise to maintain these on a part-time basis. She also cleaned the offices, and cleaned dust from healds removed from the looms.

An interesting development after World War II was the arrival in Whaley Bridge of a number of ladies from Austria to work at the mill, through the 'Blue Danube Scheme' which advertised in Austria for workers to come to Britain, initially for two years, to work in the textile industry. Some married Whaley men and stayed; one of my mother's friends was called Krystl Jones.

The manager in our era was Elliot Hurst, who had started work at Goyt Mills as a weaver in the 1920s, and had worked his way up to manager by 1952. His father, also named Elliot, had also been a weaver in North Manchester. Mr Hurst retired, age 65, in 1972, replaced by Peter Whelan, but by then the heyday of such mills was over, and it closed its doors in 1976.

Demolition in progress.

Unlike the Mevril, and the nearby Bingswood Printworks, no attempt was made to find other uses for the Goyt Mills building, and it stood empty for some years until it was demolished, along with the council-owned former gasworks buildings behind it, to make room for a housing development, christened 'Woodbrook'.

The new houses under construction: they were first occupied in 1987.

Happily, the cast iron nameboard from over the office doors was rescued by local historian Joyce Eyre, and is on display near the site of the mill gates, along with an interpretation board.

Thanks and references

Most of this piece is based on my own memories, family mementos, and my late mother's photograph collection, with help from ancestry.co.uk and other online sources.However I must thank the members of the Whaley Bridge Photos Forum and associated websites for their work in recording the history of the village I called home for 35 years.

David Stirling's Goyt Valley website is an excellent read for anyone interested in the history of the Fernilee area.

Pronunciation note: We have always spoken the name as H-you-m as is the norm in place names such as Kettleshulme, although the people of Whaley tended towards 'Oom' rhyming with 'zoom'. In Germanic countries we answer to Hull-may...Charles Hulme met my Mother, Agnes Hill in the late 1940s when they both were employed at Bennett and Jackson's Mevril Springs Bleachworks in the Horwich End district of Whaley Bridge, and they married in 1948. Agnes's father James Hill probably did not approve of the match, as Charles (also, like myself, commonly known as Charlie) frequented pubs and drank beer, anathema to the strictly Methodist Hill family, but he lived with it. I only have a fragmentary knowledge of my father's early employment; clearly he was a skilled craftsman as some of his metalworking tools - taps, die and feeler gauges, have come down to me, along with a hardened steel stamp which he made himself (exactly how, I have no idea) and was used to make his name on his tools.

The 1939 Register records him working at the Bingswood Printworks, which occupied the buildings which later became the Bingswood Industrial Estate. His job at that time was described as 'Textile printing machine minder'.

He found himself in the Cheshire Regiment in World War II, and a notebook has survived in which, in addition to notes made on training courses he noted his various postings:

September 26th 1940. Somme Barracks, Sheffield. 4133211 Private C. Hulme, [Cheshire Regiment]. 3 Squad, 2 Recruit Company, 341st M.G.T.C. [Machine Gun Training Centre] Rifle No. 3168, Bayonet 336.There are no more entries: I believe that he was discharged as medically unfit, and returned to Whaley Bridge where he served in the Home Guard while returning to work at the Bingswood Printworks, which had ceased printing in 1942, but part of the works was used to manufacture munitions for the Admiralty, not resuming printing work until 1947.

November 18th 1940: 2 M.G. Company, Bishopholme [Bishopsholme] Sheffield. During his time in Sheffield the city was heavily bombed by the Germans: In total over 660 people were killed, 1,500 injured and 40,000 made homeless.

March 21st 1941: Manchester Company, No.1 M.G. Holding Batallion, Whitley Bay, Northumberland. Whitley Bay had pretensions as a seaside resort: in the 1950s, at my father's suggestion, we spent a fortnight's holiday there.

May 24th 1941: No.1 M.G. Company, the Dale, Upton, Chester

Rifle No. 3168 handed in on June 21st 1941.

June 23rd 1941: 8th Battalion Cheshire Regiment, Caldey Manor, Caldey, Wirral. A Company. Lewis Gun. Browning Automatic. Thompson Sub M.G. Rifle No. 680017

August 19th 1941: RAF Station "Stella Maris", Formby, Lancs. (Notes about Lewis Anti-Aircraft Gun)

September 13th 1941: Frankby Hall, Frankby, Wirral. Batman. (A batman is the personal servant of an officer.)

September 21st 1941: Northern Junior Leaders School. Peover Hall, Knutsford, Cheshire. Peover Hall had been requisitioned by the Army, and later became famous as the HQ for General George Patton of the United States 3rd Army when preparing for the D-Day landings in 1944.

The family story goes that when the war ended, Charles lost his skilled job in favour of returning soldiers, and was forced to find work as an unskilled labourer at the Mevril Springs bleach works, loading yarn into the 'kiers' - tanks in which the bleaching process took place, in a foul chlorine-laden atmosphere amid the ancient equipment. (I recall that most of his evening meal conversation consisted of complaints about the foreman Mr Roberts.) The manager of the works at that time was Mr Shelmerdine, whom I know interested himself in my welfare in various ways, as did residents of Whaley Bridge in ways I didn't appreciate at the time.

I can't resist including a short piece I wrote at Whaley Bridge School in November 1955, aged 6:

My Daddy is a bleacher. He works at Bennet & Jackson. He works on a dumper. He does 150 cops until 5 o'clock, and 200 until half past nine. He is good at electric and wood-work. He goes to work at half past 7 in the morning. He comes home at 12 o'clock on Saturday morning. There are wagons and lorrys. There is a big shoot, at the top the cops are parseled up, and then sent down the shoot into a lorry.Charles Hulme married Agnes Hill in September 1948, and I was born the following year, destined to be their only child. Their first home was the Hulme family home at 5 Spring Bank Terrace, Reservoir Road, Whaley Bridge, which they shared with Charles's two sisters and niece, but soon afterwards they were able to rent their own home, a small terraced cottage at 12 Canal Street where we lived for several years before moving into the slightly large house next door at No.11, which became my home for the next thirty years. See also my pages James Hill and his Daughters and Me and Mrs Middleton.

After the bleach works ceased trading, Charles was able to find new work at the Bernard Wardle printworks near Chinley, where his job was to connect together, using a sewing machine, rolls of cloth for the continuous-roll printing processes. The heavy rolls had to be carried by hand to his work station. Hard work, and a compulsory 12-hour working day plus Saturday morning.

I owe a great deal to my father, who laboured for long hours to bring home a wage packet, which, as was the tradition, he turned over unopened to my mother who issued him and me with the week's 'spending money.' Most of my father's went on cigarettes and a daily bottle of stout, fetched from the nearby Navigation Inn. Most years in the 50s and early 60s we had a summer holiday, which was taken in 'Whaley Wakes fortnight' which happened to include my birthday. We'd travel by train to a different English resort each year, and spend two weeks using dad's 'Holidays with Pay' money on a guest house or private hotel. Our suitcases would be carefully sewn up in sacking and taken to Whaley Bridge station to travel by the Passenger Luggage in Advance system and delivered to our lodgings.

He made a hobby of woodwork, and after his marriage he made some of the furniture for our family home in a workshop which he also created himself in the back yard of our Canal Street house, complete with home-made work bench. Sadly, his physical and mental health deteriorated and by the 1960s, before I could really get to know him well, he had retreated into his shell, spending several weeks in Parkside mental hospital, Macclesfield in 1963, finally dying of cancer just after Christmas 1966. The one piece of advice I recall him giving to me was 'Never do anything unless you can face the consequences.'

Like many others of my generation, I was the first in my family to go to University after passing suitable 'A' levels at New Mills Grammar School, at no cost to my family in those days when University education was for a few, supposedly selected by academic ability. I was even able to claim from Derbyshire County Council my travelling expenses three times a year from home to London and back, and my season ticket for travel between lodgings and college. Whether I made the best of the opportunity is doubtful, as it came soon after my father's death and initially I was unable to adjust to the need to work unsupervised, preferring to explore London's rail network.

However I did eventually obtain a degree in Mechanical Engineering from Imperial College, and went on to use skills I had learned there in the early days of computing to hold down a well-paid job at the University of Manchester where we made several innovations in the sphere of library automation. Perhaps my father would be as proud of his only child today as he always was in his lifetime.

This picture of Mevril workers, showing a presentation in progress to a Mr Brown, probably the manager, in November 1954. Any other names will be gratefully received.

The Hulme family tree

What follows is based mostly on what memories I have about

the Hulme family, a few relics, and what I can glean from

the Internet.My Grandfather, Albert Hulme, was born in 1871, in the township of Eccles, Lancashire at No. 3, Smith Fold, Monton, a very small cottage, which has not survived, on Park Road near the junction with Monton Green. His father, Thomas Hulme, was born in 1808, or possibly 1811, in Fallowfield, Lancashire according to census records. Frustratingly, details of the life of Thomas Hulme before 1871 have not come to light. In 1871 he was working as a gardener, perhaps for one of the big houses in the Monton area. The family in the 1871 census comprised Thomas, his wife Elizabeth, then aged 47, and sons Edward (aged 6) and Albert (age one month).

The 1881 listing has them at 9 Partington Street, Monton. The picture above is one of a series in the Digital Salford collection taken in 1961 when the houses in Partington Street were being demolished. I believe this one shows No.9, whose occupants appear to be holding out against the bulldozers. The site was converted to a car park, which remains in 2017.

Thomas was then 73 and his wife Elizabeth 57. Edward is not listed, but there is Charles Hulme, age 14, cotton weaver, born in Eccles, appears along with Albert (aged 10). Thomas died later in 1881, and the family dispersed. It seems unusual that Elizabeth had given birth to Albert when she was aged aged 47, but it is confirmed by his birth certificate.

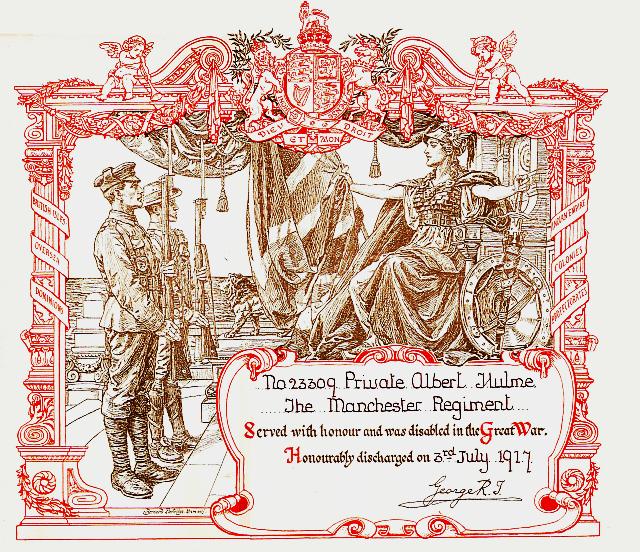

My Grandfather Albert, at the age of 16 in 1887, enlisted in the Army, and his records have survived, so I know he was 5 feet 4½ inches tall, with fair complexion and blue eyes (like me), chest measurement 33 inches, weight 199 pounds. His next-of-kin. widowed mother Elizabeth was by 1887 living at Railway Terrace, Eccles. A Private in the Manchester Regiment, he served for some years in India, and saw action when the 2nd Battalion of the Manchesters was one of the units ordered to put down a rebellion in the Miranzai Valley on the North West Frontier with Afghanistan. This 'Miranzai Expedition' lasted from 3-25 May 1891. He was entitled to the 'India General Service medal 1854 with Samana clasp', but I do not know the whereabouts of this. He returned to Britain in 1895, and left the Army in 1899.

Back in civilian life, he needed a job, and seems to have become an itinerant labourer. The family story is that he arrived in Whaley Bridge while working on the laying of gas mains, and decided to stay after getting to know local resident Sarah Ellen Bates, who became his wife in 1902. I believe he also worked on the construction of Christ Church on New Horwich Road, opened in 1903 (and converted to a house in 1997).

Albert and Sarah Ellen set up home in the end cottage of Spring Bank Terrace, Whaley Bridge, close to the Railway station, at 8 Reservoir Road, later re-numbered 5. They had three children, all of whom appear in the 1911 Census: Marion Hulme (b.1905), Beatrice Hulme (b. 1907) and my father Charles Hulme, born in August 1910. The house was one of several bought as a rental investment by Henry Fawcett Middleton.

Albert found a job in a local quarry, until he 'answered the call' in the Great War and returned to the Manchester Regiment. He signed the Attestation in January 1915, when aged 45 years and 10 months, and was sent into the horrors of France with the Second Battalion on 4 May 1915. At this time the Battalion were part of the Indian Corps, engaged in the Second Battle of Ypres where they came under attack by poison gas as well as machine-gun and shell fire. In September 1915 the Manchester took part in the battle of Loos, where gas weapons were deployed by both sides: The British suffered more than 40,000 casualties - of which some were their finest troops (and included 3 major-generals) - with gas casualties of around 2,600, and 7 gas related deaths. The total German losses were only around 20,000, with estimates of 600 deaths due to gassing.

In November 1915, due to the heavy casualties sustained by the Indian Corps, it was decided to withdraw it from the western front. They travelled by train Marseilles and sailed in the troopship SS Huntsend (the German passenger ship Lützow which had been siezed by the British in the Suez Canal in 1914) reaching Basra, in Iraq, then known as Mesopotamia, on the 8 January 1916. There, they took on the Turkish army in the relief of the siege of Kut Al Amara (7 December 1915 – 29 April 1916), also known as the First Battle of Kut. An 8,000 strong British-Indian garrison was besieged in the town of Kut, 100 miles south of Baghdad, by the Ottoman Army, and other actions. In summer 1917, while the battalion was being held in reserve, he was assessed as no longer physically fit for active service due to rheumatism, and discharged with a small pension. He found work as a 'light labourer' with William Plant of Market Street, Whaley Bridge.

I was told that he never really recovered from his wartime experiences, but he appears to have recovered sufficiently to obtain a job at the Bingswood printworks as a 'textile printing upkeep(?) labourer' according to the 1939 Register, by which time he was aged 71. He died in 1943, some years after Sarah Ellen who died in 1937.

I do have some mementos of him: his First World War medals and certificate, as well as a 'trench art' bracelet adorned with bullets and Belgian coins. There were also few Indian coins in my father's small (home-made) box of heirlooms; I later gave them to a coin collector.

The Bates family

My Grandmother, Sarah Ellen Bates, was born in 1868 in Whaley Bridge. Her father, Charles Bates, listed in 1871 as 'Gardener and Grocer' was born in 1836 in Barwell, Leicestershire, and her mother, Ann, was a native of Siddington, Cheshire. By 1901, The family was living in a row called 'Forester's View' on Macclesfield Road. Charles, by now a widower, was still a 'gardener (domestic)' and Sarah Ellen was acting as housekeeper.

Her brother, my great-uncle, Eli Bates (born c. 1873) became well-known locally as the Horwich End's postmaster, running the Post office in the end house of Willow Terrace on Buxton Road, built in 1888, with his wife Martha. He died in 1934, as did Martha later that year. The shop, now 139 Buxton Road, has housed various business since the Post Office was relocated to another shop nearby. In 2017 it is the home of 'Cloud Wines.'

After Sarah Ellen left to marry, Charles and his son John (Warehouseman, Bleach Works), looked after themselves in the house in Foresters View; Charles lived until 1926. His daughter Mary Ann Bates married Alfred Pickup, and I knew something of Pickup family relatives in Whaley Bridge in my time, although as I recall there were religious differences. We were never close friends with anyone on the Bates side of the family.

Bottom Lodge

A caption in the book Goyt Valley Romance by Gerald Hancock mentions a 'Mrs Pickup' who ran a shop at the Bottom Lodge, Goyt Valley. It would appear that this 'Mrs Pickup' was my great-aunt Mary Ann Pickup, née Bates, and that her brother Eli also lived there at some time. She died in 1930; we have, however, not found any documentary confirmation of Mrs Pickup's shop, which would have been in the 'gap' between the 1911 census and the 1939 Register. Any information is very welcome.

On the back of our picture (above) of her brother Eli's Post Office someone has written ‘E Bates 1928 / from Bottom Lodge, Goyt Valley / Moved to Start Lane?’. Bottom Lodge stood, we believe, on the road (known as the Valentine) from Long Hill down to the Fernilee Gunpowder Works at the point where it crossed the track of the Cromford and High Peak Railway (closed in 1892). Top Lodge, at the top of the same road, was ' a tiny gatehouse made of dressed stone' where according to Joyce Winfield in her book The Gunpowder Mills of Fernilee William Simpson and his wife Letitia brought up three children in the building which had no supply of water, gas or electricity. Gerald Hancock identified an image of this building as Bottom Lodge, which we believe to be an error.

There is no trace of the Bottom Lodge building today, it was destroyed during the construction of Fernilee Reservoir dam in the 1930s. It stood close to the later 'Reservoir Cottages' which were built for water board workers maintaining the reservoir. This detail from a photograph of the dam construction work shows what we believe to be Bottom Lodge, circled. It lay in the angle between the Cromford and High Peak railway trackbed, seen running across the view, and the road leading down towards the abandoned powder mill and on to Errwood. The 1891 census refers to 'powder mill road - railway crossing' as its location.

My Hulme Aunts

A brief biography of Charles's two sisters is appropriate. The picture is from a family holiday, around 1951-2. Marion Hulme (left), myself, Beatrice Hulme, Agnes Hulme, Charles Hulme.

Marion Hulme ('Aunty Fanny' as I knew her as a child), like many girls in Whaley Bridge, started work at the age of 12 in the Goyt Mill cotton weaving shed; the law at that period permitted this child labour on a part-time basis. Initially, she would have done menial jobs, but developed the skills to be come a full-time weaver, eventually tending twelve looms. Born in 1906, she did this skilled job amongst the noise and dust until she retired at the age of 60, not long before the mill closed. I recall the carriage clock, which she received as a reward for 48 years of 'clocking-on', in pride of place on the dresser of her front room. She married Walter Lamb in 1953, and they moved to 55 Chapel Road, Whaley Bridge.

My mother and I would visit them often when I was young, but after my father died in 1966, visits became less frequent. Walter Edward Lamb (born in 1887), who when younger had, I believe, worked in the Fernilee Gunpowder works, was a local postman when I knew him. He was born in Macclesfield, son of Walter Edward Lamb and Lydia Lamb; I remember him as a cheerful and likeable character. They had no children, as they had married late. Walter Lamb died in 1973. Marion died in 1981; to my shame I did not attend her funeral.

Beatrice Hulme ('Aunty Beatty') born also worked in the Goyt Mill, but I recall that her job was a less skilled one: a sweeper, if my memory is correct. Borm in 1908, she died in 1977, and my mother and I did attend the funeral. She lived all her life in the house an 5 Reservoir Road, along with her daughter Ivy, plus - for a short while my mother and father - and later her son-in-law John Edward Hollingworth and her grandson. The house made news one day in the 1950s when it was struck by lightning. I remember going in there the day after; the house was not greatly damaged, but all the electric sockets had been blown out of the walls.

On the steps of 5 Reservoir Road, circa 1956: Back row from left: Walter Lamb, Charles Hulme, Ivy Hollingworth, John Hollingworth. Front from left: Marion Lamb, Charles Hulme, Agnes Hulme, Beatrice Hulme.

My cousin Ivy, born in 1935, was much older than me. She married John Edward Hollingworth at Taxal Church in 1956. Born in 1933 to John R Hollingworth, a worker at the Disley paper mill, and his wife Sarah, John Edward worked for the railway as a shunter at Gowhole sidings, and I recall the traditional 'seeing off' to the honeymoon with decorations, balloons and 'Just Married' signs applied to a railway compartment! Shunting goods wagons ws a dangerous job, and John had to leave it after his arm was crushed between two wagons. They had one son; John died in 2000 and Ivy in 2014.

Charles Hulme, my Great-uncle

About my namesake great-uncle, Charles Hulme, I do know some of his life story, which catches my attention through my interest in railways.He left the cotton trade for a career as an 'iron driller' in a famous locomotive works, James Nasmyth's Bridgewater Foundry in nearby Patricroft. The 1911 census has him aged 44 at 12 Victoria Street, Patricroft with his wife Elizabeth Hulme (43), their son Albert Edward Hulme (23) labourer in the loco works, John Hulme (21), engine cleaner, probably at the nearby Patricroft locomotive shed, daughter Elizabeth Hulme (20) cotton polisher, and younger daughters Hilda Hulme (10) and Lily Hulme (born June 1907). They had been married 23 years, and none of their children had died.

Charles died in 1936. The 1939 Register shows Elizabeth as a widow (occupation: retired velvet dyer) living at 33 King Edward Street, Patricroft with her daughter Lily Green, her husband Herbert Frederick Green and their children. Lily had married Frederick (as he was always known) in 1929; he was born in 1901, the son of an ironstone miner from Lincolnshire, and died in 1955. Frederick worked, like his father-in-law, at the nearby Bridgewater Foundry, which in 1940 was requisitioned by the Government as a Royal Ordnance Factory. In 2017 an industrial estate occupies the site and some of the former buildings, served by a new street called James Nasmyth Way. Frederick and Lily, with their daughter Audrey, attended my parents' wedding in 1948 and I have a childhood memory of travelling to Patricroft on one occasion to visit them, but we were never a close family.

Written by Charlie Hulme, Updated April 2024. Comments welcome at info@nwrail.org.uk